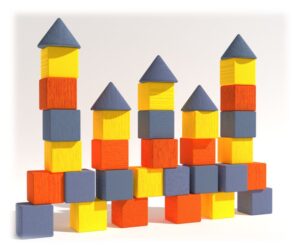

To understand why adults on the autism spectrum can experience interaction difficulties in their relationships, it is important to understand childhood social development. Social development is a term that describes the development of social skills and the emotional growth that are required in order to relate to others and build relationships with them (Bushwick, 2001; Smith & Hart, 2002). Social development also includes the development of empathy and an understanding of the needs of others. Social development provides the building blocks to create successful social relating and interaction throughout the lifespan. Starting from birth, typically developing children mature through following a consistent pattern that occurs in stages. Like all learning, social learning is cumulative which is a multiplicative process, not an additive one. New skills acquired at each stage enable the learner to perceive and understand experiences in a way that makes construction of the next stage possible (Bushwick, 2001). Just like building blocks that need to be positioned in order to support following blocks, the next stage of social development is not able to be accurately acquired until the skills of the previous stage have been correctly mastered. Typical social development produces improvement in the understanding and knowledge of human beings, providing insight into how human beings function which makes them more interesting, and in turn, encourages a preference to a attend to people rather than the non-social environment (Bushwick, 2001). For individuals with on the autism spectrum this is not the case. They often attend to the non-social environment and their social development misses many crucial links in the social learning chain through the different wiring of their brain. Not joining in with social interactions or imitating others as they grow and develop also hinders crucial links in the social learning chain. Missing some of these critical elements can create many learning gaps. These gaps have the potential to lead an individual with autism down the path of developing either detached or dependent behaviours, or both, within their adult relationships. Although higher functioning adults with autism usually have average or above average intelligence, they will always experience life-long difficulties with social interaction and social behaviour.

Gaps in social learning

One such crucial gap in the social learning chain is spontaneous mimicry (imitation or mirroring), including facial mimicry, and is important for socio-emotional skills such as empathy and communication (Oberman, Winkielman, & Ramachandran, 2009). This process is supported by several brain systems. Studies on the brain have found that imitation is a complex process between visual processing, working memory, motor control, sequential organization, and learning. Individuals with autism fail to develop normal patterns of social interaction due to missing out on the insight gained from this non-verbal imitative learning. Not looking equals not learning.

Another significant gap in the social learning chain is reading faces (Macdonald et al., 1989). Facial expressions are an outward display of an inward emotional state. They can be processed both explicitly (consciously) and implicitly (unconsciously). Facial expressions are powerful nonverbal displays of emotion, which signal important emotional information to others, and contain information that is vital in the complex social world. Many aspects of successful social interaction involve processing information from faces in order to recognise social cues like emotional expressions, lip speech, and eye gaze. Not looking at the faces of others can lead to unclear conversation and problems relating to others.

From when children on the autism spectrum are small, they are less likely to look at other people, are less likely to smile and vocalise at others, and tend to look at the mouth rather than eyes, missing much of what is happening around them. Looking at faces and imitating others is a critical part of what makes us cognitively human for much of our success rests on our ability to learn from others’ actions. Reciprocal social interaction requires that there is adequate appreciation of social–emotional cues shown by responses to others’ emotions, use of social signals, and socio-emotional reciprocity. In order to understand intent in everyday interactions it is important to rely on cues such as facial expression and tone of voice. An inability to link perception of faces to the retrieval of social knowledge, makes reciprocal social interaction challenging. Without looking at the face or recognising why a particular tone is used, the likelihood that interactions would be filled with misunderstandings intensify, which escalates a potential for conflict.

Another crucial gap in the social learning chain is joint attention. Joint attention is using gestures and gazes to share attention concerning objects or events in order to comment on the world to another person, as in “Look at that!” Joint attention becomes a bridge to coordinate perceptions with others while sharing new experiences. When people instinctively follow the gaze of other people, this joint attention helps promote social bonding, enhance learning, and may even be necessary for the development of language. Typically developing children use the Speaker’s Direction of Gaze (SDG), a component of joint attention, to learn language and communication skills. SDG consists of looking at the eyes of the speaker and then in the direction of the speaker’s gaze. Children on the spectrum use the alternative, the Listener’s Direction of Gaze (LDG) (Baron-Cohen, Baldwin, & Crowson, 1997). In other words, they keep looking at what they were originally looking at, causing them to miss the object of interest and the speaker’s intention. The absence of SDG in autism goes some way toward explaining the unusual development of language in autism. The resulting communication errors have the potential to create significant obstacles for adult relationships.

Another learning gap for individuals on the autism spectrum is pretend play (Barry & Burlew, 2004). Research has concluded that the developmental stages through which children usually progress, specifically, a child’s ability to socially coordinate free play with peers, is a necessary building block to being able to establish successful interpersonal connections later in life. Social coordination works in conjunction with an understanding of the perspectives of others. When recognising other’s possible misunderstanding, typically developing children compensate by checking through asking questions. An absence of asking questions can create misunderstandings.

By the age of four, children also develop three critical domains of social behaviour; attachment, instrumental interaction and experience-sharing (Gutstein & Whitney, 2002). The first two stages; attachment and instrumental interaction are usually achieved by those on the spectrum, however, the final more mature stage; experience-sharing commonly is not fully attained. Research defines experience-sharing as relying on abilities to constantly reference the emotional states and actions of others and being able to base one’s own actions on ongoing evaluations of what is taking place. Lacking this key area of social development can result in two-way misinterpretations of events. In social situations with others, adults with autism can send the ‘wrong’ message with the result that others can get the wrong impression; concluding that the person with autism is disinterested, angry, or hasn’t heard them, leading to communication breakdown.

Misinterpreted messages require a further necessary element for emotional coordination, which also develops at age four. This is the ability to repair misunderstandings, conflicts, and social and emotional discord. Research reveals that people on the spectrum have fewer social-repair mechanisms in their toolbox. However, adults ordinarily are expected to share equally in maintenance and repair of a relationship. Within relationships that are evenly balanced, there is an appreciation for the other’s perceptions and perspectives, even if different, with a willingness to accept others’ shortcomings. The lack of fluency in the foreign language of social interaction can hinder the comprehension required to share and coordinate experiences and truly participate in a well-adjusted reciprocal partnership.

The difficulties experienced by adults in their relationships are often traceable to poor social and communication skills created by a lack of interest in participating in the observation of, and imitation of others, while also missing out on the necessary early learning typically gained from early childhood social development. The result of being deprived of many of these crucial links in the early social learning chain is to become an adult who has had a lifetime of relationships littered with misunderstandings, misinterpretations, and social interaction mistakes. While early intervention is important for children on the spectrum to support their social learning life throughout their lifespan, awareness of the needs of adults on the spectrum is just as important.

Dr. Bronwyn Wilson

References

Baron-Cohen, S., Baldwin, D. A., & Crowson, M. (1997). Do children with autism use the speaker’s direction of gaze strategy to crack the code of language? Child Development, 68(1), 48-57. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1131924

Barry, L. M., & Burlew, S. B. (2004). Using social stories to teach choice and play skills to children with autism Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 19(1), 45-51.

Bushwick, N. L. (2001). Social learning and the etiology of autism. New Ideas in Psychology, 19(1), 49-75. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0732-118X(00)00016-7

Gutstein, S. E., & Whitney, T. (2002). Asperger Syndrome and the development of social competence Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 17(3), 161.

Macdonald, H., Rutter, M., Howlin, P., Rios, P., Le Conteur, A., Evered, C., & Folstein, S. (1989). Recognition and expression of emotional cues by autistic and normal adults. Journal Child Psychology Psychiatry, 30(6), 865-877.

Oberman, L. M., Winkielman, P., & Ramachandran, V. S. (2009). Slow echo: facial EMG evidence for the delay of spontaneous, but not voluntary, emotional mimicry in children with autism spectrum disorders. Developmental Science, 12(4), 510-520. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00796.x

Smith, P. K., & Hart, C. H. (2002). Blackwell handbook of childhood social development. Oxford, UK ;: Blackwell Publishers.